Toshiaki Toyoda is a screenwriter and director born in Osaka Prefecture in the 70s and which is part of the shinjirui. While still a high school student, Toshiaki was destined to become a professional shōgi player and it’s thanks to this passion that he entered the world of cinema by participating, in 1991, in the writing of the script for Sakamoto Junji’s film Checkmate whose characters are shogi players. In 1996, he worked again with this same director on the film Billiken before making his debut, alone, behind the camera with his first feature film Pornostar (ポルノスター). Released in 1998, Pornostar is a visually impressive and nihilistic story that features a man anxious to eliminate the yakuza that he perceives as dangerous and above all useless to society. In 2001, Blue Spring (青い春) was released, which followed angry, directionless high school students and explored their social dynamics. And it was in 2003 that Toshiaki Toyoda closed this trilogy of films that focuses on angry young people, their virility and the strangers of society with 9 Souls (ナイン・ソウルズ), a film in which the director combines the black comedy of his first film with the rich characterization of the second without sacrificing his aesthetics and punk side. It’s with these films that the director gives an overview of his vision of society and distinguishes himself in the lost Japanese decade of the 90s with this triad.

A new one in the Yakuza genre.

The yakuza eiga (ヤクザ映画 or ヤクザえいが), or yakuza film in French, is a genre that focuses mainly on the relationships and life of the Japanese mafia. Namely that there are two subgenres: the Ninkyô eiga, chivalric, idealistic and formalistic films with a moralizing dimension that emerged in the 60s and the Jitsuroku eiga, anarchist films, more violent and more realistic because they are based on true stories that appeared in the 70s. And when we think we have seen everything with Kitano, Suzuki, Akira Kurosawa, Kinji Fukasaku or Takashi Miike, Toshiaki Toyoda also scores a big hit in the yakuza genre with his first feature film: Pornostar.

Pornostar is a nihilistic film with dark comic and poetic moments mixed with this punk image in which the director portrays a juvenile and irrecoverable Japanese society under the influence of the yakuza in the hot neighborhoods of Tokyo. Between 1997 and 1999 the number of members and associates experienced a very slight increase and although the yakuza were very present at that time and influenced part of the young society, they were not unanimous and we can see it with the character of Arano. In his film the director shows the mafia proud to shout their belonging to a certain group and distribute flyers for recruitment. The bands organized in Japan are trivialized. Toshiaki Toyoda deals with the case of an adolescent in distress through the framework of the yakuza and their rotten networks well established in society.

In his film, the character of Arano is a mysterious young man, almost catatonic sociopath, marginal manipulated by those he hates and embarked in the rhythm of life of unsavorable characters that are the Kamijiro gang. All against a stunning and noisy punk-rock music background. Arano hangs out with infamous characters and young aspirants of the Japanese underworld who think they have control over the latter by using him to do the dirty work. In this film women are only secondary, almost uninteresting and often ignored, there is only room for violence and we can see it when Kamijiro does not move when a woman kisses him and ignores her proposal to go to the Grand Summer of Love, to go elsewhere, further than this suffocating city gnawed by cruelty and crime.

It is a violent and raw first film with an opening scene that, thanks to the music and camera work, shows us this rebellious spirit, this devastating and murderous side that accompanies and embodies this character who arrives in slow motion in front of us like a human time bomb. A world in which only violence reigns and where every man seems to be a yakuza or about to become one. A society dominated by crime that makes Arano fall into a spiral of violence, instability but above all a search for identity. We are talking here about the search for identity but especially a goal because Arano does not really have one and the leisure activities of modern life (arcade, skateboard…) are not enough to compensate for his miserable existence. A violent man who will try to soften with Alice, a woman obsessed with him and who represents what is sweet in this world despite the scene with the portable CD player and drugs.

But this lightness is only a facade. He’s the darkest thing in a destructive man who was aimlessly eliminating the uselessness of society and highlighting the void left through a generation as well as all the social and economic problems of past decades. In the end, it is Arano who is seen as someone useless to society before leaving in an unequal and lost fight in advance. A first dark film that announces the color of those to come.

The source of imagination and creativity is anger. There is a deep anger in me. It doesn’t fade. Society is always irrational. – Toshiaki Toyoda.

« People who know what they want scare me.”

« This violence of high school students is not only a Japanese phenomenon, it’s present everywhere, it’s international. What distinguishes that of Japan may be due to the following :on the one hand, the bands that are created in high schools sing the yakuza model with a boss and two lieutenants. « – Toshiaki Toyoda

In his second film, Blue Spring, released in 2001, Toshiaki Toyoda points the finger at an angry and desperate youth where violence and suicide are the only escapes, witness of absenteeism and self-harm, against a punk-rock style soundtrack. We follow these young people without direction by exploring their social dynamics. Being without direction and not being guided is shown through the lack of adults and especially teachers. The few teachers in this high school flee violent students and we see it in the intro scene where a teacher runs screaming, while students chase him, before fleeing in a taxi in front of the school. This creates a kind of spiral where, surely because of their social background, young people turn to violence and no longer follow classes. They are less and less interested, which no longer motivates teachers who abandon students who try to cope with the fact of being abandoned by associating with figures who impose a form of respect and admiration. For them, the yakuza are an image of success and they want, or at least try, to resemble them by imitating the model of the Japanese Underworld with a leader and lieutenants.

It is a film with young people adrift and an almost non-existent educational system that pushes them to violence and crime, which can be seen with the scene where Yukio kills one of his comrades with a knife. There is a parallel with Kitano’s Kids Return released in 1996 where two young people who drop classes and seek to be respected enter this gear of violence by becoming either boxers or mobsters. Teachers are desperate and no longer try to help them because they are lost causes for whom it is useless to do anything more since they will not do anything with their lives. They end up being those young people without direction represented with the scene where he goes around in circles on a bicycle in the courtyard, without any specific goal.

But the abandonment of these young people in difficulty, in Blue Spring, goes as far as the abandonment of this place of education that becomes a dilapidated prison more than a high school. But not all teachers abandon students, like the gardener’s character, Hanada, who tries to give them benchmarks, advice and educates them through flowers. The only beautiful thing that young people maintain with care in this dark high school. Even after the murder committed by Yukio, Hanada does not let him go, going so far as to run after the police car or run to the building to help and rescue Aoki on the edge of the void. He does not forget that despite the nonsense they can do, with different degrees of importance, remember, they remain no less children. The director does not forget to give us this reminder by putting a photo of baby Yukio after his murder, as if to tell us that despite this, he was a young man who needed help. And this is the general atmosphere of this film, there is despair, a cry for help that makes the atmosphere dark and unhappy. These young people with bad acquaintances and without a correct model who follow what the older ones do, take care of themselves only among themselves (we can see it in this scene on the roof where Kujo, the main character, cuts his friend’s hair) and put themselves in danger by testing their virility, their courage and their fear with a game where they clap their hands in the void. Game that will go too far until the suicide of Kujo’s best friend who will not be able to save him in time.

Through all this, Toshiaki Toyoda wonders if society would not do better if young people stripped adult control and were in power. Thanks to this film we understand that for the director it is not possible, it seems to suggest that too much damage has already been caused. Young people in difficulty will always need the help of an adult to be guided, their social environments must not be a brake on their future and crime is not a solution. For Toyoda, youth finds it good to be angry but should not be caught in a spiral by following bad examples, it should not be let down either.

Juvenile delinquency skyrocketed during the decade, which began in 1993, with the economic deterioration following the bursting of the speculative bubble in 1980. Toyoda is close to this youth and can show with great empathy the society’s lack of interest in these young people who come from disadvantaged backgrounds. It helps the bourgeois more than the students in need who are not taken into account by the authorities. A universal problem which does not only concern Japan.

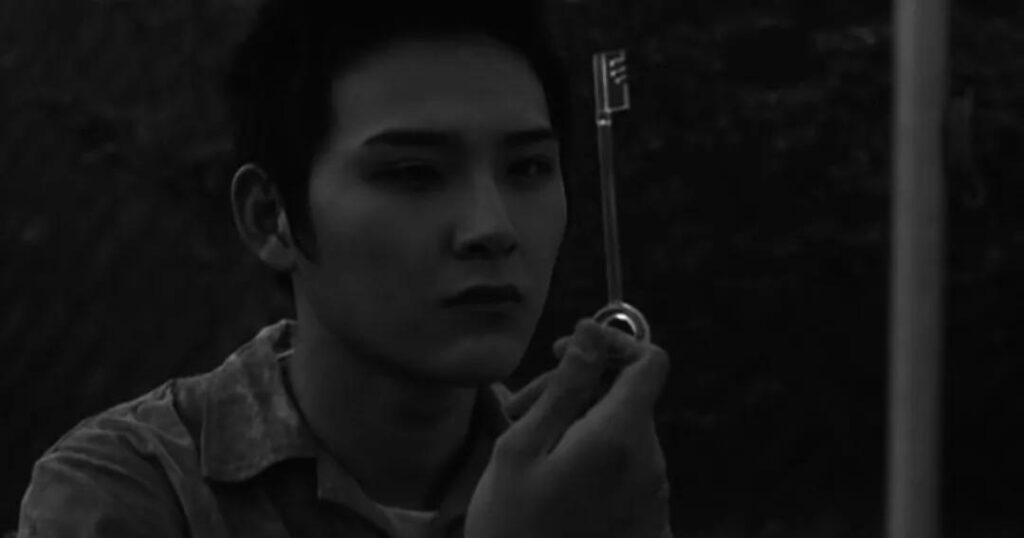

The key to the future that opens every door.

In his third film, 9 souls, we follow a band of criminals with different personalities, strengths and weaknesses. Young people who also differ in age, education and especially in the crimes they each committed. Toyoda uses the funnel technique in his film where from the start we address the general subject with the prison and escape scene and then follow the individual presentation of all the characters. As the film progresses, the message becomes more important; by relying on the lives of the characters and people they had to leave behind when entering prison and those who will enter their lives afterwards. It is a film in which prisoners seek redemption, each in their own way for those who still think it is possible.

At the beginning of the movie they are just lost souls who don’t know where to snay. They are marginalized who no longer correspond to society’s expectations because of the isolation and community life they have created among themselves in prison. They face freedom in a comical way which gives some crazy scenes like this moment when the nine prisoners all invited themselves to a partner of Torakichi without embarrassment and without understanding why it bothers his wife so much. They are no longer in line with the company that no longer integrates them or struggles to do so. We see a little of their previous life, their confrontation with their past and attempts at reintegration. This creates empathy between us and the characters, we feel a certain closeness and that’s what the director wants. To know if we look at these people as prisoners or as simple humans, souls. Would we grant redemption to these nine souls, would we forgive their crimes? There is an existential void in this film.

Toyoda uses differences to his advantage and shows it via disguise. The disguise suggests a new beginning, a new person. They are no longer those men they were in prison, they are trying to change to integrate again but they are outcasts considered dangerous and assimilating themselves to a group is not as simple as rejected. It is possible to integrate as we can see with Ichiro Ushiyama who disguises himself and becomes a waiter because he fell in love with a woman. But their harsh personalities and their problem, of anger for some, resurface at one time or another. Anger or revenge, each its own engine. Revenge is more embodied by the youngest of the new to whom the key to the future is given. As if adults knew that the best, for those who still have life ahead of them, was to move forward and be able to open all the doors, seize the opportunities. As mentioned above, this film is existential because it addresses a subject that will always be relevant despite the past years. Depending on the crime committed, will we look at a man for what he really is and for what he is trying to become or for what he has done in the past. Toyoda shows us that a prisoner remains a man with a soul who can be in love and who wants to change. It is easier for them to escape from prison than to flee their past. In the city and in society in general, the penitentiary is still present, wherever they go.

Early films tend to go towards youth dramas with a focus on delinquents. However, with 9 Souls, we see something much more complex. The film manages to balance the same intensity of previous works with elements of surrealism and comedy while addressing the subject of the prison system by questioning rehabilitation and the possibility of finding a place within a community. His absurd humor is not only there to defuse or to have empathy, the director enters into an anti-manichean approach of « it’s not all white, it’s not all black ». Finally, Toshiaki Toyoda is interested in marginality and these people that Japanese society has put aside

Merci Noah/@n0ah287 pour la relecture Lien de l’article en français

Laisser un commentaire